With dramatically increasing scrutiny on the Thai fishing industry in recent years, the Thai government and private sector have launched wide-ranging initiatives in an attempt to reform historically unregulated practices and prevent the exploitation of the industry’s workforce. While they have taken a number of encouraging steps, there remain significant gaps, particularly with regard to the government’s system of inspections. Our report, Assessing Government and Business Responses to the Thai Seafood Crisis, provides an independent, field-based assessment of the reforms in the Thai fishing industry, and offers practical recommendations for improvement.

Fundamental to the abuses exposed in Thailand’s seafood industry is a failure of regulation, both in design and enforcement. Recent changes have sought to address a poorly managed labour market with high numbers of informally employed migrant workers, an absence of controls at Thailand’s ports, a failure to monitor vessels at sea, impunity for illegal practices, and an opaque chain of custody from vessels to factories that has made tracing fisheries products nearly impossible.

To address these challenges, the Thai government has introduced sweeping legislative and regulatory reforms that, on paper, are some of the most comprehensive measures the industry has ever seen. But implementation has been inconsistent, both in ports and at sea. Inspection systems are underfunded, plagued by corruption, and constrained by inadequate vessel monitoring capabilities. More importantly, inspectors have failed to identify victims of forced labour, as they lack the resources and incentives to check crews and interview workers.

Complementing the government response, the private sector has also been active – most notably through the establishment of the Shrimp Sustainable Supply Chain Task Force. The Task Force has set goals to establish credible tracing and auditing systems, develop a model code of conduct, and drive regional fishery improvements. It has achieved significant progress in some areas, but there are questions about its longevity, its voluntary compliance structure, and the degree to which it is meaningfully involving NGOs and worker representatives.

While the recent flurry of government and private sector initiatives is welcome and encouraging, it is vital that reform efforts are realistic, properly funded and monitored, and embedded for the long term in industry practice. Given the scale of the challenge and the ongoing gaps in regulation and traceability, both government and business should refrain from issuing premature claims that Thailand’s forced labour problem has been solved. Only with a sustained effort from all those involved will the livelihood and dignity of workers and the sustainability of Thailand’s fisheries be protected.

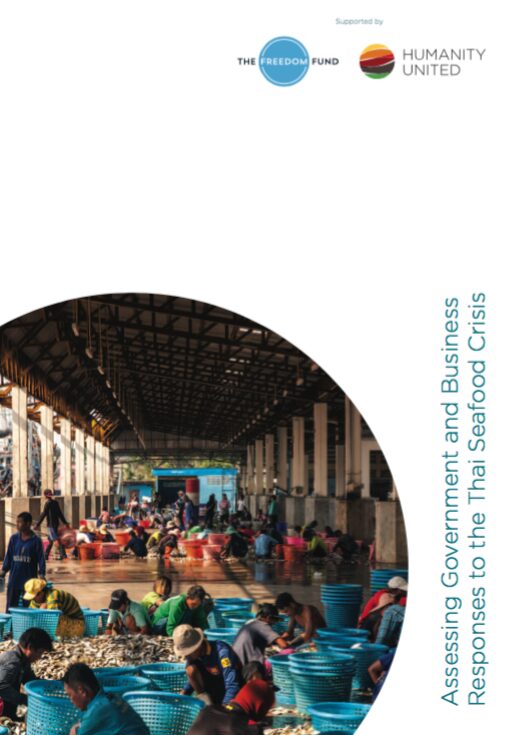

Credits: Josh Stride © Humanity United