I am just back from a short week in Lebanon talking to UN agencies, NGOs, and civil society groups about their knowledge of the extent to which Syrian refugees are vulnerable to – and have fallen into – slavery and related practices.

The most revealing part of the visit was a short trip to the town of Zahle, in the Beqaa Valley, on the east of Lebanon along the border to Syria, which is now home to hundreds of thousands of refugees. Women and girls make up the majority of refugees there and elsewhere, many men having stayed in Syria or fallen to the ever-lasting conflict. They live in informal tent settlements erected on private agricultural lands across the valley. These lands are rented by Syrian men, called Shawish, who settled long before the war started, and are themselves renting from Lebanese landowners, initially for cultivation, increasingly to provide a place to set up tents. The size, level of crowdedness and degree to which sanitation provisions have been made vary between the settlements, but the scale of the issue was made very apparent when we drove along a small dirt road on both sides of which between 15,000 and 20,000 people are estimated to be living, under makeshift arrangements. The needs for food, shelter and health services are enormous, and the snow expected to fall in two days makes the situation even more dire.

In Zahle, a Lebanese organisation called Beyond Association runs a large program of support and outreach amongst refugees, with funds from UNICEF. They showed us around their safety zone, an enclosed area organised around 8 big tents where children receive a variety of services. On that Saturday morning, each tent was filled with young children who had come to engage in various activities, from formal and life skills education, to media and music clubs and psychosocial and health counseling. In the tent where the 6/7 years old were gathered we asked who worked; all raised their hands. One after the other, they explained that they were going out to the fields to pick potatoes and onions or to construction sites to lay and cut bricks with electrical equipment. Child labour is not common, it’s rampant and from the conversations we’ve had seems to easily qualify as what the International Labour Organization classifies as ‘worst forms’: heavy loads, low pay and dangerous working conditions for the youngest.

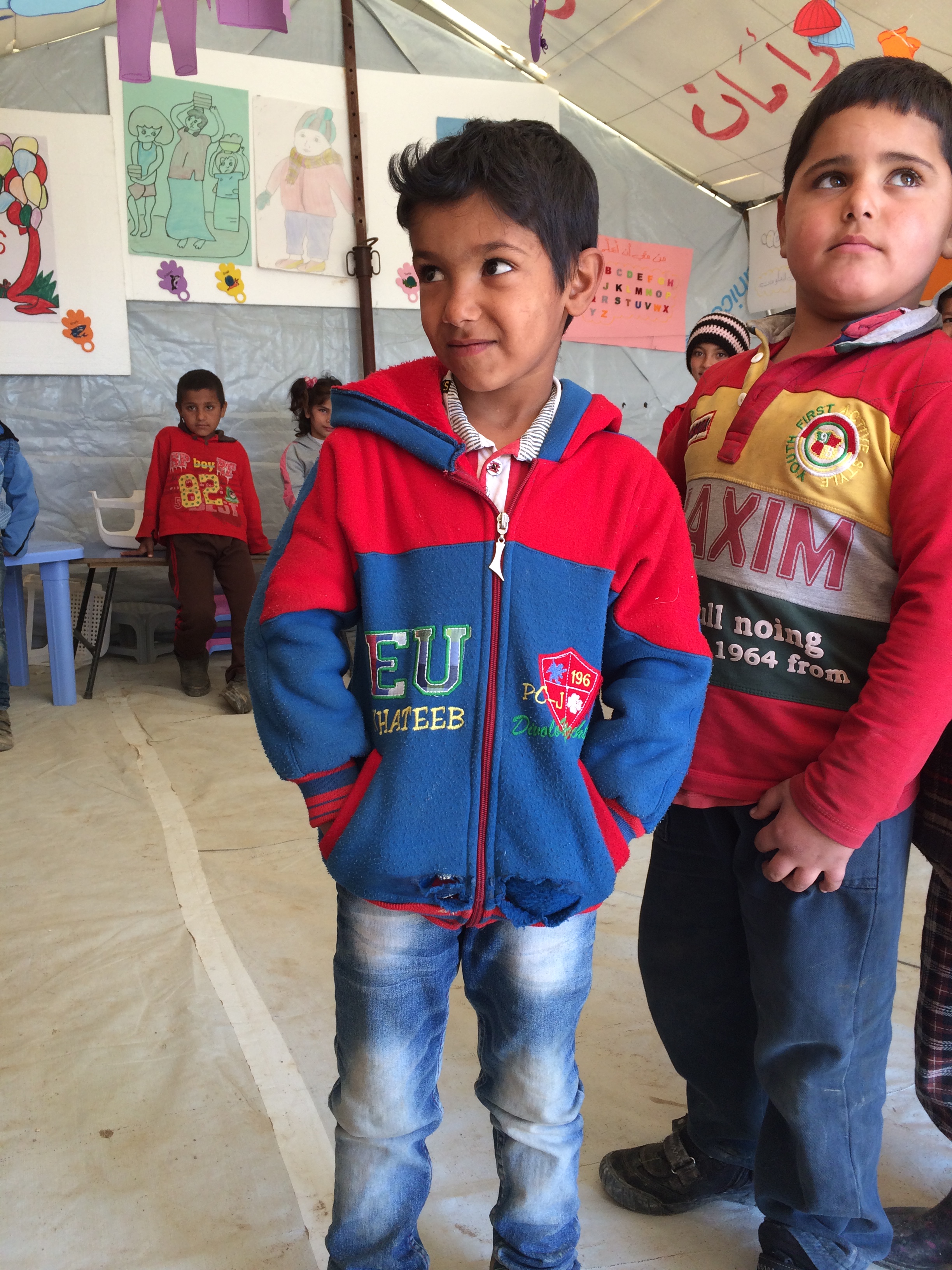

Photo: Firas is seven years old and works laying and cutting bricks when his father is unable to go. Credit: The Freedom Fund

Under the Lebanese law, adult refugees are not allowed to work and all individuals above 15 years old also have to pay a $200 residency fee per year, which very few can afford. Adults are as a result unable to work for fear of being arrested by the authorities on their way to the field or construction sites. Families have no choice but to send children. Shawish play a key role in sustaining that economy: if a farmer or a construction site owner needs labourers, the shawish will recruit them amongst those who reside on his land. By practice, each tent is expected to provide one worker. Children earn a pittance, the shawish takes a cut from it. Beyond Association has made a number of key gains by encouraging shawish to increase the minimum age for recruiting children, but the scale of the problem is enormous and the legal and structural factors pushing for this to happen leave little space for alternatives. As one NGO worker put it, if nothing is done, “this practice will soon be accepted by Lebanese society as the norm”.

Sadly, this is not all for children in the settlements of Beqaa. We also heard of the many cases of girls married at a very young age, because their family could not afford to keep them, because it was seen as a safer solution for their future or simply because the degree of despair and frustration in these communities means that it enables gender-based violence to thrive. Yet again, with intensive interventions, results can be achieved, and Beyond managed for example to reduce the number of child marriages in one targeted community from 17 marriages of girls under 14 years old in one year to one marriage of a girl under 18 the following year.

It is hard to even start to imagine what these children have gone through, yet they showed a clear commitment to learning, working less, being able to live as children and aspire for a brighter future back in Syria. Until this is possible, action needs to be taken to lift the structural factors leading to children being forced into these situations of labour and early/forced marriages and for the good community level interventions that are proving to work to be scaled up in order to meet the severity and scale of the problem.

It is also critically important for the international community to prioritise efforts to prevent the slavery and exploitation of Syrian refugees, including by requiring the Lebanese government waive the $200 residency fee and enable refugees to work legally.

Main photo: The Beyond Association safety zone in Zahle. Credit: The Freedom Fund.